nord-americà Steven Greer.

El Centre d’Estudis Interplanetaris, CEI (Centro de Estudios Interplanetarios, Centre for Interplanetary Studies), és una associació sense ànim de lucre dedicada a l'estudi dels Objectes Volants no Identificats, OVNIS creada a resultes de l’interès despertat a Barcelona l'any 1957 per la celebració del Congrés Internacional d’Astronàutica i pel llançament soviètic del primer satèl·lit artificial Sputmik I.

dijous, 22 de març del 2018

L'ésser d'Atacama era una nena amb greus mutacions genètiques

nord-americà Steven Greer.

dimarts, 2 de desembre del 2014

Empremtes dins d'un meteorit de possible activitat biològica a Mart

dijous, 29 de maig del 2014

SETI: Declaracions contundents que busquen finançament

El director del centre SETI a la Universitat de Berkeley, Califòrnia, Dan Werthimer i, l'investigador Seth Shostak, han indicat que el temps en què aquests èxits es puguin assolir només depèn "del finançament del qual es disposi per a aquest aspecte en les pròximes dues dècades".

Amb aquesta sol·licitud, aquests investigadors pretenen que l'executiu nord-americà " revisi " els avenços científics que podria suposar un descobriment d'aquestes característiques.

"Si hi ha unes 10.000 civilitzacions emetent senyals de ràdio en la nostra galàxia, caldrà observar, almenys, un quants milions de sistemes estel·lars per trobar-ne una d'elles. Gràcies a les millores en la tecnologia usada pel SETI, l'institut serà capaç de fer-ho en els propers anys ", ha indicat Shostak.

El consens científic és que la recerca de vida intel·ligent en altres mons s'ha de concentrar en aquells planetes que orbiten a una distància que han batejat com a zona habitable, és a dir, una regió en què l'aigua pugui romandre líquida.

Els científics calculen que a la Via Làctia hi ha 800.000 milions d'estrelles. Només el telescopi espacial Kepler ha descobert més de 1.700 planetes a la zona habitable. No obstant això, Shostak ha apuntat que la recerca no només s'ha de concentrar en galàxies llunyanes.

"També podríem trobar vida microbiana molt més a prop, a Mart o en una de les llunes de Júpiter i Saturn, que semblen tenir aigua, ja sigui en la seva superfície o sota d'ella".

La qüestió, esmenta, és construir l'equip i finançar els científics per realitzar la cerca."Els mètodes per trobar vida impliquen el desenvolupament i llançament de naus que puguin perforar la superfície de Mart, o una que obtingui una mostra dels guèisers de les llunes Europa i Encèlad", han explicat als seus interlocutors al Congrés.

dissabte, 30 d’abril del 2011

La recerca extraterrestre frenada per la crisi

La recerca d’extraterrestres també es frena per la crisi l’Allen Telescope Array (ATA), el principal complex de radiotelescopis del qual disposava per a la cerca i anàlisi senyals de ràdio extraterrestres. Aquest interferòmetre astronòmic de 42 antenes ubicat a a Hat Creek (Califòrnia, Estats Units), es va fer molt popular arran de la pel•lícula Contact , amb l’actriu Jodie Foster com a protagonista.

Tom Pierson, director executiu de l’Institut SETI, subrratllà en un comunicat que els telescopis havien deixat de treballar degut a la reducció dels fons públics que contribuïen al manteniment. No és un tancament definitiu, precisà, sinó que s’estava treballant per a aconseguir altres fonts de finançament. L’ATA, es constituí gràcies a una milionària donació de Paul Allen, cofundador de Microsoft, ha estat gestionat per l’Institut SETI i la Universitat de Califòrnia a Berkeley, a més d’aportacions menors procedents de l’Estat de Califòrnia i de donants particulars. Ara bé, els fons públics, que són la part essencial del pressupost, s’han reduït enguany a una dècima part.

diumenge, 16 de gener del 2011

Un article publicat en una revista de la Royal Society vol un pla de l´ONU per a contactes amb alienígenes «violents»

La revista argumenta que si el procés d'evolució segueix a tot l'univers patrons darwinistes, tal com passa a la Terra, les formes de vida que contactarien amb els éssers humans podrien «compartir la seva tendència a la violència i l'explotació» dels recursos. Per aquest motiu, els científics reclamen que les Nacions Unides (ONU) configurin un grup de treball dedicat a «afers extraterrestres» amb la capacitat de dibuixar un pla per seguir en cas d'un contacte alienígena. «Hem d'estar preparats», en cas de coincidir amb una civilització extraterrestre, segons el professor de paleobiologia evolutiva a la Universitat de Cambridge Simon Conway Morris, que considera que la vida biològica ha de tenir a tot l'univers unes característiques similars a les de la Terra.

Morris creu que si hi ha alienígenes intel·ligents «seran semblants a nosaltres», cosa que, «atesa la nostra no gaire gloriosa història», hauria de "fer-nos reflexionar". Altres científics, com els professors John Zarnecki, de l'Open University, i Martin Dominik, de la Universitat de Saint Andrews, reclamen un pla "responsable" dirigit per experts i científics que eviti els «interessos de poder i l'oportunisme en cas que els extraterrestres arribessin al nostre planeta».

La possible falta de coordinació que presumiblement es donaria en aquest hipotètic encontre amb extraterrestres s'ha d'evitar, segons aquests científics, amb la creació d'un marc general de treball que sorgiria d'un «esforç veritablement global governat per un grup polític amb prou legitimitat».

Font:

EFE/ Regio 7, 7 de gener de 2011

dissabte, 30 d’octubre del 2010

El 23% de les estrelles podria tenir planetes similars a la Terra

Els investigadors van escollir 166 estrelles dels tipus G i K (els més semblants al Sol pel seu espectre lluminós) i que estiguessin a un màxim de 80 anys llum, i a continuació van enfocar cap a aquestes estrelles amb el poderós telescopi Keck (Hawaii). Van utilitzar tots els mitjans de rastreig disponibles actualment. La fecunda recerca, els resultats de la qual s'han publicat a la revista Science, va acabar amb la detecció de 33 planetes (més 12 de no confirmats) en un total de 22 sistemes solars.

Els astrònoms no van observar cap planeta com el nostre -la mida va oscil·lar entre 3 i 1.000 masses terrestres-, però sí que van constatar que els més petits eren justament els més nombrosos. En l'1,6% de les estrelles van trobar cossos de la mida del gegant Júpiter; en el 6,5% hi va haver planetes amb una mida compresa entre Neptú i Urà, i en l'11,8% van aparèixer les anomenades súper-Terres, amb una massa entre 3 i 10 vegades la del nostre planeta.

«Si extrapolem cap a planetes amb una massa compresa entre la meitat i dues vegades la massa terrestre, podem predir que en trobarem 23 per cada 100 estrelles», diu Howard. Marcy hi afegeix: «Les dades ens diuen que la nostra galàxia, amb els seus 200.000 milions d'estrelles, té almenys 46.000 milions de planetes de la mida de la Terra, sense comptar els que hi pogués haver lluny de la zona considerada habitable (ni molt a prop ni molt lluny de les seves respectives estrelles)».

Els resultats desafien l'anomenat «desert planetari», una hipòtesi que manté que hi ha pocs planetes rocosos a la zona habitable perquè la proximitat d'un sol els fa físicament impossibles. És molt possible que alguns no hagin sobreviscut, precisa Ignasi Ribas, investigador de l'Institut d'Estudis Espacials de Catalunya (IEEC), però alhora és «lògic» que hi hagi molts més planetes petits perquè per a la seva formació es necessita menys material. «Això ja s'havia previst amb diversos models teòrics», afegeix.

Ja es coneixen 490 exoplanetes. «Quan arribin durant la pròxima dècada les noves tècniques d'exploració -conclou Howard- potser no caldrà buscar gaire lluny per trobar altres terres».

Font:

Antonio Madridejos. «El 23% de les estrelles poden tenir planetes similars a la Terra». El Periódico de Catalunya (30 d'octubre de 2010).

dimarts, 24 d’agost del 2010

Vida extraterrestre: no com la imaginem

Tal és la conclusió d’un dels principals astrònoms del SETI, l’Institut per a la Cerca d’Intel·ligència Extraterrestre, amb base a Califòrnia, Estats Units.

Segons el doctor Seth Shostak, l’organisme fins ara ha buscat senyals de ràdio procedents d’altres mons semblants a la Terra.

Però potser els extraterrestres ja han passat del desenvolupament de tecnologia de ràdio i han aconseguit un nivell d’intel·ligència artificial.

L’astrònom afirma en la revista Acta Astronàutica que avui en dia tenim més possibilitats de detectar aquesta intel·ligència artificial que formes de vida biològica.

Durant molt de temps els científics que treballen en el SETI han argumentat que la naturalesa potser ja es va encarregar de resoldre el problema de com sostenir vida amb distints models de compostos químics.

És a dir que els extraterrestres no sols no serien com nosaltres, sinó que ja no es troben al mateix nivell biològic amb el qual funcionem els habitants de la Terra.

Com nosaltres?

Tot i això els científics del SETI han basat les seves recerques en la teoria que els extraterrestres podrien ser éssers «vius» tal com nosaltres.

Certament, el que estem buscant al cosmos en un objectiu que evoluciona i està en moviment

Per això, aquesta cerca de vida ha seguit algunes regles bàsiques de la bioquímica com un període finit de vida i procreació. Però sobretot ha estat subjecta als processos de l’evolució.

Ara, no obstant això, el doctor Shostak afirma que encara que l’evolució per a desenvolupar éssers capaços de comunicar-se més enllà del seu propi planeta pot tardar molt de temps, la exotecnologia podria haver avançat prou ràpid per a «eclipsar» a les espècies que la van crear.

«Si observem les escales de temps del desenvolupament de tecnologia, veiem que en un punt es va inventar la ràdio i després vam ser capaços de transmetre senyals i vam tenir la possibilitat que algú ens escoltés» va explicar el científic a la BBC.

«Però uns centenars d’anys després d’haver inventat la ràdio – almenys si ens posem nosaltres com a exemple – podríem inventar màquines que pensen, la qual cosa és quelcom que potser aconseguirem aquest segle».

«Així hauríem estat capaços d’inventar als nostres successors i només durant uns quants centenars d’anys hauríem estat una intel·ligència 'biològica'», indica.

Des del punt de vista de la probabilitat, agrega el científic, si aquestes màquines pensants van aconseguir evolucionar, tenim ara més possibilitats de detectar els seus senyals que les de la vida «biològica» que les va inventar.

Objectiu en moviment

Per la seva banda John Elliot, el qual fou investigador del SETI i ara treballa a la Universitat Metropolitana de Leeds, a Anglaterra, afirma que els comentaris del doctor Shostak expressen un sentiment comú en la comunitat de científics de l’Institut.

"Hem de partir d’alguna cosa i no hi ha res incorrecte en aquesta teoria", diu el doctor Elliot a la BBC.

«Però després d’haver cercat senyals de vida durant 50 anys, el SETI està travessant un procés de conscienciació sobre la forma com la nostra tecnologia ha avançat, la qual cosa és un bon indicador de com altres civilitzacions – si és que existeixen – podrien haver progressat».

«Certament, allò que estem buscant al cosmos en un objectiu que evoluciona i està en moviment», afirma el científic.

Però ambdós investigadors estan d’acord en què trobar i desxifrar qualsevol eventual missatge que pogueren enviar aquestes màquines pensants podria ser més difícil que si es tractés de vida biològica.

La idea, no obstant això, ofereix noves direccions en la cerca de vida extraterrestre.

Segons el doctor Shostak és probable que la vida extraterrestre artificialment intel·ligent emigri cap a llocs on tant la matèria com l’energia, les úniques coses que serien d’interès per a aquestes màquines, estiguessin plenament disponibles.

Això significa que la busca del SETI necessita enfocar-se prop de les estrelles joves i calentes o , fins i tot, a prop del centre de les galàxies.

«Crec que hauríem de dedicar un percentatge del nostre temps a buscar en les direccions que potser no siguin les més atractives en termes d’intel·ligència biològica, però que podrien ser on s’ubiquen les màquines que pensen», afirma el científic.

Font:

BBC, 23 d'agost de 2010

diumenge, 8 de febrer del 2009

Nou treball científic sobre probabilitat de vida extraterrestre

Segons el professor Duncan H. Forgan en l’article «A numerical testbed for hypotheses of extraterrestrial life and intelligence», la troballa en anys recents de més de 330 planetes fora del nostre sistema solar ha ajudat a depurar el nombre de formes de vida que és probable que existeixin. No obstant això, és poc probable que puguem establir contacte amb mons extraterrestres.

Aquesta no és la primera vegada que científics proposen càlculs generals sobre la probabilitat de vida intel·ligent en l’univers. El mateix article parteix de la celebèrrima, equació de Drake. Entre els càlculs d’estimació aproximada més recents s’han proposat nombres que van entre un milió i u.

Durant més de 50 anys hem estat descobrint planetes fora del nostre sistema solar assenyala el professor Forgan de l'Institute for Astronomy, University of Edinburgh. Fins estos moment s’han descobert 339 planetes individuals, però la xifra augmenta ràpidament

Per als seus càlculs els investigadors va ser crear una simulació informàtica basada en el mètode de Monte Carlo. D’aquesta manera van obtenir sistemes solars a partir de la informació que es coneix sobre l’existència dels anomenats exoplanetes descoberts en a distàncies relativament properes. Aquests mons extraterrestres simulats van ser després sotmesos a nombrosos escenaris distints.

Per exemple, en un es va assumir que és difícil que es formi vida però és fàcil que evolucioni. I amb açò es va trobar que podria haver-hi 361 civilitzacions intel·ligents en la galàxia.

Un segon escenari va assumir que es pot formar vida fàcilment però hi hauria molts problemes per a desenvolupar intel·ligència. Sota aquestes condicions els investigadors van calcular que poden existir 31.513 formes de vida.

L’últim escenari va analitzar la possibilitat que la vida podria passar d’un planeta a un altre durant col·lisions d’asteroides. Aquesta popular teoria la forma com es va formar la vida en la Terra es coneix com panspèrmia. Aquest enfocament va donar com resultat l’existència de 37.964 civilitzacions intel·ligents.

No obstant això, tal com hi ha assenyalat el professor Forgan, el principal problema és que s’ignora realment com va començar la vida. A la Terra hem hagut de fer moltes suposicions sobre com es va formar la vida i aquest ha estat el primer escull. Si s’aconseguís superar aquest obstacle i establir quins planetes podrien tenir vida i els que no, potser es podria definir un patró de l’evolució en aquets planetes.

De totes les maneres hi ha moltes variables que continuen sent només estimacions aproximades. Per exemple, el temps des que es va formar un planeta fins al moment en què va aparèixer la vida i d’ací fins que va sorgir la primera civilització intel·ligent. Ara tenim valors aproximats.

El professor Forgan afirma que per als seus càlculs han assumit que la Terra és un planeta en valor mitjans, la qual cosa si bé és una consideració raonable no exclou la possibilitat que es tracti d’una situació marginal. I és que fins ara només tenim una sola referència real, que és el planeta Terra.

I encara si existeix vida en altres planetes, això no necessàriament significa que puguem entrar en contacte amb ells perquè no sabem com seria aquesta forma de vida. L’estudi de Forgan el que fa és prendre els estudis passats sobre civilitzacions extraterrestres i en redueix el marge d’error. És a dir, es pot quantificar la nostra ignorància de forma més efectiva.

diumenge, 3 d’agost del 2008

La NASA afirma haver analitzat aigua marciana

«Tenim aigua», va assegurar el passat dijous en una roda de premsa a la Universitat d'Arizona a Tucson Wiliam Boynton, el principal investigador de l'equip que gestiona l'aparell del laboratori de la Phoenix Lander que ha identificat el líquid. Aquest enginy és una espècie de forn que escalfa els materials recollits pel braç robòtic de la Phoenix i n'analitza els vapors.

En dues ocasions anteriors aquest braç va recollir mostres de gel, però no va ser capaç de fer-les arribar al laboratori perquè van quedar atrapades a la pala que les recull. El dimecres 30, en canvi, el braç va recollir en una excavació a cinc centímetres de profunditat una altra mostra que sí que va poder entregar.

El gel havia passat gairebé 48 hores exposat a l'aire, i per aquest motiu part de l'aigua de la mostra s'havia vaporitzat, cosa que en facilitava el maneig. Quan es va col·locar a l'analitzador de gasos i es va començar a escalfar el gel es van detectar pics en els punts que corresponen a la presència d'aigua.

Segons va declarar el dijous un altre dels científics de la Universitat d'Arizona, Peter Smith, està «totalment convençut» que tenen aigua a les mans.

Boynton va anar més enllà i va sentenciar, sense donar peu a cap mena de dubte, que «és la primera vegada que es toca aigua marciana».

Malgrat l’alegria dels científics, encara és aviat per a si el gel alguna vegada s'arriba a fondre prou i si hi ha components químics amb carboni i altres materials per albergar vida.

Dijous, els investigadors de la NASA van marcar un termini de tres o quatre setmanes per començar a obtenir respostes i van advertir que, de moment, no han trobat cap mostra de materials de tipus orgànic. «Intentem entendre la història del gel – va explicar Smith – i determinar si alguna vegada va estar fos i va poder formar un ambient líquid que va poder modificar el terreny».

De moment, la troballa ha animat la NASA a allargar cinc setmanes la missió de la Phoenix Lander, que va arribar al pol nord marcià el 25 de maig i que havia de finalitzar la feina a finals d'agost. Ahir es va anunciar un increment d'1,3 milions d'euros al pressupost de 269 milions que finança l'operació, que es prolongarà dels 90 dies marcians inicialment previstos fins als 124.

Font:

agències i premsa, 31 de juliol i 1 d'agost de 2008

divendres, 8 de desembre del 2006

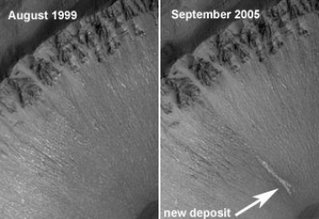

L´aigua líquida trobada a Mart suggereix que el planeta està actiu

La troballa d´evidències «recents» de la presència d´aigua líquida a Mart, a partir d´imatges captades per la Mars Global Surveyor (MGS) de la NASA, suggereix per primera vegada que és un planeta «actiu» capaç de remodelar la seva superfície i que, de fet, ho ha estat fent durant els últims anys. Segons experts en geologia marciana, el descobriment dels científics de la NASA, que publica avui la revista Science, és innovador perquè per primera vegada s´ha determinat «que recents» són les rases dibuixades per l´aigua fluint en els vessants dels cràters del planeta vermell.

Les fotografies preses en 2004 i 2005 per la MSG mostren dos dipòsits de sediments brillants situats en vessants de cràters que suggereixen que l´aigua hauria arrossegat material en algun moment durant els últims set anys. El geòleg del Centre d´Astrobiologia (CAB) Jesús Martínez-Frías va explicar que ja es coneixien evidències de la possible existència d´aigua en el passat de Mart, gràcies a imatges de torrenteres i altres empremtes en la superfície, però no se sabia que Mart era actiu des d´un punt de vista geomorfològic.

El nou treball apunta que l´aigua líquida hauria emergit a la superfície i hauria fluid «breument» pels vessants abans d´evaporar-se o congelar-se.

Segons Martínez-Frías, la troballa és «una altra peça més per identificar potencials àrees d´interès a Mart», i encara que sí existeixen evidències que hi podria haver aigua subterrània, es desconeix encara si aquesta és «freda o calenta», i si la vida seria possible sota de la superfície.

Font: Diari de Girona (8 de desembre de 2006).

dijous, 7 de desembre del 2006

La Nasa obté proves que hi podria haver aigua líquida a Mart

D'altra banda, el president del laboratori de San Diego que ha coordinat els treballs d'investigació va assenyalar que es van adonar que hi podria haver líquid a la superfície perquè les imatges aèries canviaven a mesura que anava passant la sonda. L'aspecte canviant d'aquests rierols fa sospitar que l'aigua podria estar amagada al subsòl del planeta.

Fins ara la Nasa només tenia proves que hi havia hagut aigua a Mart fa milions d'anys. Aquesta nova prova obre noves possibilitats de cara a poder realitzar la primera missió tripulada al planeta més proper a la Terra.

A la imatge de l'esquerra de 1999 no es veu el possible dipòsit d'aigua que sí apareix el 2005.

Imatge ampliada del que podria ser el dipòsit d'aigua.

Font textual: Avui (7 de desembre de 2006)

Font gràfica: www.nasa.gov (6 de desembre de 2006)

dijous, 23 de novembre del 2006

The New Search for E.T.

Night watch: The new telescope at Oak Ridge Observatory, in

It doesn’t look like much: just a clapboard shed in a clearing, surrounded by tall pines. No plaque or other marking announces what goes on here. Inside stands a 4-meter-tall black metal frame covered in Mylar, looking sort of like a giant’s box kite waiting for a stiff breeze. Beneath the shroud of plastic are a largish mirrored disk, a second smaller mirror, and some cables and electronics.

Suddenly, the roof begins to glide backward on steel tracks, revealing the night sky overhead. Even as the contraption tilts slowly into place, its exact angle controlled by a computer in the next room, the true purpose of this unassuming apparatus might be unclear to the casual observer. But it constitutes the most sophisticated implementation of a concept that a few technologists, including me, have been pushing for more than four decades—a telescope dedicated to answering an age-old question: Is anybody out there?

With the unveiling last April of this new facility, the search for extraterrestrial intelligence, or SETI, entered a new era. Most previous SETI attempts have listened for radio signals, but after more than 40 years, none has detected anything of significance. This telescope—designed by Harvard University physics professor Paul Horowitz and his colleagues and constructed at the Oak Ridge Observatory, in Harvard, Mass., about 50 kilometers northwest of Boston—takes a new tack [see photo, “Night Watch”].

Horowitz is hunting for the briefest pulses of visible light that a far-off civilization could be sending toward Earth. His is the first telescope to be specially designed and dedicated to this purpose, and, many experts now agree, it represents the right direction for SETI to take. If E.T. is trying to talk to us, he’s probably beaming light our way, not radio waves.

It’s been said that the most important event in human history will be when someone discovers that we earthlings are not alone in the universe, that there are other beings smart enough to let us know they exist. For most of our history, the technology to look for extraterrestrial life was beyond our means. But the relatively recent advent of large dish antennas and extremely sensitive receivers gave us the tools to listen for radio frequency signals.

Starting in 1960, radio astronomers have mounted dozens of SETI experiments, some lasting only a few weeks or months, others running for years. Most of these searches were targeted at nearby star systems, those thought most likely to harbor life, while others encompassed the entire sky.

The two longest-running SETI projects to date,

Project Serendip, meanwhile, is tuned in only to 1420 megahertz, the frequency of the neutral hydrogen atom, which is the most abundant substance in the universe and can be readily detected, even by small telescopes.

But neither

One reason for that failure is the sheer complexity of the task. Our galaxy contains more than a hundred billion stars, spread across an expanse of almost 100 000 light-years. The recent discoveries of extrasolar planets—which number more than 200 at last count—boost hopes that there is intelligent life out there. And yet, as astrophysicist and SETI pioneer Frank Drake famously postulated in equation form, the likelihood that any one of those billions of star systems hosts not only a habitable planet but also one that has evolved beings who are both willing and able to communicate with us is quite low.

Low, but not zero. If you assume, for example, that one in a million stars has a planet bearing intelligent life, that means our galaxy is home to at least 100 000 advanced civilizations. Even if only one in a hundred million stars qualifies, that still leaves more than 1000 civilizations that could be trying to contact us.

To date, though, radio astronomers have heard nothing. It’s too soon to conclude that nobody’s out there: maybe SETI researchers are just looking in the wrong place or in the wrong way. I believe they’ve made the latter mistake. No intelligent society would attempt to communicate with us over hundreds of light-years using radio waves when physics suggests other wavelengths would be the more intelligent choice.

As far as we know, only two types of waves can travel through the vacuum of space: electromagnetic and gravitational. Gravitational waves would be exceedingly hard to generate or detect, so any signals headed our way will probably lie somewhere in the electromagnetic spectrum—from X-rays at one extreme to frequencies lower than an ordinary AM radio at the other end. For years, the SETI community rejected the idea of looking for anything other than RF signals, even though they represent just a tiny portion of the electromagnetic spectrum [see illustration, “Casting a Wider Net”]. Limiting SETI to just radio waves is like losing a diamond ring on a football field and only searching for it at the 1-yard line.

A good argument can be made that the optical spectrum is a more likely place to find alien signals than are either RF or microwave frequencies. For one thing, it’s much easier to deal with noise at optical wavelengths. People who measure radio waves have to contend with interference from radar antennas, radio stations, and other terrestrial sources. The receiver itself also adds noise, which is why the detectors attached to advanced telescopes are typically cooled to near absolute zero. Yet there is always some residual thermal noise to contend with, and for certain wavelengths the cosmic microwave background—a vestige of the big bang—makes SETI searches difficult.

For optical observations, the only significant terrestrial source of interference is lightning, which is at worst a sporadic problem. In the early days, many investigators discounted optical SETI because they imagined that the sender’s star would be an overwhelming noise source. But they didn’t appreciate that it is actually quite easy to arrange a transmission that outshines whatever sun you’re circling: just use a pulsed laser rather than the continuous-wave type.

The development of laser communications systems for military satellites, submarines, and aircraft has proved that short bursts of light are far more efficient than continuous waves at carrying information over great distances. Each pulse has a high peak power, but most of the time the laser isn’t active, so the overall power consumption is low.

Presumably a distant intelligent civilization would have figured this out as well. With transmissions in brief bursts, each pulse could easily be 1000 times as bright as any nearby star in the receiving telescope’s field of view. The shorter the pulse, the less background light there is per pulse to compete with the signal. Reducing the pulse to nanosecond intervals makes the signal even more distinct, because there’s no source in nature that generates flashes that short.

The sender could vary the interval between pulses to convey information. Think of each interval as a roulette wheel. Each slot in the wheel represents a number: if the pulse fell in slot 36, it would be conveying the number 36; if it fell in slot 1, it would mean the number 1. The roulette wheel could have more or less than 36 slots, of course, and as the number of slots changes, so does the amount of information you can send per pulse. With just two slots, you could send just one bit per pulse; with 256 slots, you could send 8 bits; and with 1024 slots, you could send 10 bits. This technique, called pulse-position modulation, was used for many years in both radio and optical communications. So, if you were to detect a pulsed signal coming from space, the next step would be to analyze it for any repeating sequences.

Another reason to prefer optical methods over radio SETI is that it’s much easier to form a narrow beam of light. Remember, any message will have to travel many trillions of miles through space to reach us. If the sender were to broadcast a signal in all directions at once, the power needed would be prohibitively high, regardless of what wavelength was used.

George W. Swenson Jr., professor emeritus of astronomy and of electrical and computer engineering at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, has calculated that if a radio transmitter were 100 light-years away and projecting its energy omnidirectionally, it would require 5800 trillion watts to provide a detectable signal—an amount, Swenson points out, that is “more than 7000 times the total electricity-generating capacity of the U.S.”

SETI researchers therefore generally assume that the transmitter will point toward specific star systems and that the beam will be as tight as possible. The ratio of the wavelength being transmitted to the diameter of the antenna used is roughly proportional to the width of the beam. And the wavelength of visible light is six orders of magnitude smaller than that of microwaves, allowing the beam to be considerably narrower. So the physics of optics over RF wins out again.

Charles Townes—the coinventor of the laser—and Robert Schwartz first suggested the idea of searching for optical signals from extraterrestrials in 1961. Their paper, published in Nature, theorized that beings in a nearby star system, “some few or tens of light-years away,” could use laser (or maser) beams to communicate with us earthlings.

It took several more decades for optical SETI to catch on, in large part because laser technology wasn’t nearly as mature as radio technology. That’s no longer the case. Photodetectors today have quantum efficiencies of 40 percent or more; that is, for every 100 incoming photons, 40 are actually counted. The detectors are also much faster now, and picking up nanosecond pulses is no problem.

The new Harvard telescope takes advantage of these and other technological advances. Unlike a regular imaging telescope, Horowitz’s brainchild has no lens, nor is it designed to pluck pristine images of celestial bodies orbiting overhead. Its mission is a bit cruder. It uses a 1.8-meter-diameter mirror and a 0.9-meter secondary mirror to scoop up raw photons from the sky—much as a wooden barrel collects rainwater. For that reason, the telescope is more properly, though less glamorously, known as a photon bucket [see photos, “A Closer Look”].

Photon buckets are less expensive to build and operate than imaging telescopes, because all you’re really worried about is that the photons arrive at the detector. If a given photon ends up traveling a few extra millimeters because it hit an air pocket in the atmosphere, it doesn’t really matter. An advanced imaging telescope, by contrast, employs all kinds of sophisticated mechanisms to compensate for distortion in the incoming signal, so that it can accurately reproduce what it sees.

A key feature of the Harvard telescope is its use of multipixel photomultiplier tubes. Photomultipliers work by converting incoming photons into electrons, which then get amplified until the electrical signal can be distinguished from the noise. A multipixel photomultiplier divides the collection area up into tiny squares—64 per tube in this case—each acting like a separate detector. This setup lets you look at more star systems at a time.

The Harvard telescope breaks up the sky into 1.6- by 0.2‑degree patches, observing each patch for about 48 seconds before moving on to the next patch. A mere 48 seconds doesn’t sound like a long time, but remember that the associated electronics are sampling the data in nanosecond intervals. At that rate, the instrument should be able to cover the entire sky above the northern hemisphere in 150 nights of observation.

All those signals from all those pixels are then fed into 32 microprocessors, which were custom-designed for the project by Horowitz’s graduate student Andrew Howard. These PulseNet chips crank through the data—3.5 trillion bits per second—searching for a large spike in the photon count, which may indicate a possible light pulse from afar.

The telescope’s photodetectors are divided into two arrays, so that if one of them receives an interesting signal, you can check it against the second array. Ideally, you’d like to have an entirely separate telescope. In a previous search, Horowitz collaborated with David Wilkinson’s group at

The Harvard photon bucket isn’t looking at any particular wavelength, but SETI investigators have long speculated that intelligent beings would choose to send their signals at a special frequency, one that is somehow fundamental to the universe. If we knew what that frequency was, it would narrow our search dramatically, because we’d have to observe just a tiny fraction of the spectrum. That’s why Project Serendip and a number of other radio SETI efforts focused on the hydrogen line.

In the optical regime, there are equally interesting frequencies that an intelligent civilization might choose. Called Fraunhofer lines, these are naturally occurring gaps or holes within the spectrum of visible light given off by stars. At these frequencies, the stars’ background energy drops considerably—in some cases, to only one-tenth its normal value. So if an alien sent a signal at the wavelength of a Fraunhofer line, the transmitter wouldn’t have to be nearly as strong, and at the receiving end, the search for the correct wavelength would be greatly simplified.

The operators of the Harvard telescope assume that the transmitter is pointed our way continuously. But what if the source is transmitting only sporadically—pointing toward our solar system for a few nights, say, and then moving on to another star system? Only a lucky coincidence would have everything lined up at exactly the right time. Yet, the only way to cover the entire sky at once would be to construct many thousands of receivers, each looking in a different direction.

And what if the alien’s signal requires a much larger receiver than what we currently have? There are several options here. You can simply build a bigger photon bucket, which would increase the collection area and thus boost the number of incoming photons. Or you could network together lots of smaller telescopes. Stuart Kingsley, an optics engineer and SETI enthusiast, and I proposed such a scheme several years ago.

We were inspired by the enormous popularity of the SETI@home program, which is harnessing the power of 5 million personal computers to crunch through the data collected by SETI radio telescopes.

Our proposal involved using hundreds or even thousands of amateur telescopes, equipping each of them with a low-cost photodetector and then aiming all of them at a given star system at the same time. Of course, each telescope would be a slightly different distance from the star, but you could compensate for those differences by using a GPS receiver to pinpoint each telescope’s position to within a few centimeters. You would also need an Internet connection to some central control center, which could collect all the data and coordinate when the telescopes were observing and where they were pointed.

For the best observations, though, you would need to place your telescope out in space. Earth places some limits on how sensitive a detector you can build. Manufacturing and maintaining a telescope’s large mirrors is costly, and wind vibrations and the pull of gravity also constrain the size of the apparatus. What’s more, the atmosphere filters out photons of certain frequencies, and you can’t observe at all in cloudy weather.

A photon bucket out in space or on the moon, by contrast, would experience low gravity and no wind (although the solar wind is still a consideration). You could therefore construct it from lightweight materials, so it could be much larger than any terrestrial receiver. And, of course, there would always be clear weather.

Such endeavors, though, will have to wait for a generous benefactor to come along. Nearly all of the SETI research today is funded by individual donors or by nonprofit groups, such as the Planetary Society, in

Font: Monte Ross, IEEE Spectrum (Novembre 2006).

divendres, 14 d’abril del 2006

Two telescopes join hunt for ET

Optical astronomers scan the sky for signs of life.

The search for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI) will ramp up in coming months as two dedicated facilities come online — one to look, the other to listen.

A team led by physicist Paul Horowitz of Harvard University will begin scanning the skies this week for flashes of light from alien civilizations. Most SETI searches have been at radio wavelengths, but theorists surmise that extraterrestrials might also shine laser beacons visible from a few thousand light years away.

This will be the first optical SETI project to scan the entire sky, or at least all that can be seen from the Oak Ridge Observatory in Harvard, Massachusetts, where a 180-centimetre telescope has been installed. The $50,000 instrument was paid for by the Planetary Society, a grassroots group of space enthusiasts, and will record flashes briefer than a nanosecond. No known natural process causes such flashes. The all-sky search requires 200 nights of clear viewing, and is expected to take several years.

Meanwhile, at the Hat Creek Radio Observatory in northern California, the first ten dishes of the privately funded Allen Telescope Array are due to be demonstrated later this month, says Peter Backus, observing programmes manager at the SETI Institute in Mountain View, California. With money from Microsoft alumni Paul Allen and Nathan Myhrvold, the institute, working with Berkeley, is building an array of 350 six-metre radio dishes dedicated to SETI. The entire array will eavesdrop on nearly a million stars for hints of intelligence.

Managers hope to have 42 antennas working by July. The first scan will be of a narrow swathe of the Milky Way's centre.

Font: Nature vol 440, 853 (13 April 2006)

dimecres, 8 de febrer del 2006

Space rock re-opens Mars debate

The material resembles that found in fractures, or "veins", apparently etched by microbes in volcanic glass from the Earth's ocean floor.

Details will be presented at the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference in Houston, Texas, next month.

All the processes of life on Earth are based on the element carbon.

Proving carbon in Martian meteorites is indigenous - and not contamination from Earth - is crucial to the question of whether life once arose on the Red Planet.

Initial measurements support the idea that the "carbonaceous material" is not contamination, the scientists say.

The research team includes scientists who brought evidence for microbial life in another Martian meteorite, ALH84001, to the world's attention in 1998.

The Martian meteorites are an extremely rare class of rocks. They are all believed to have been blasted off the surface of the Red Planet by huge impacts; the material would have drifted through space for millions of years before falling to Earth.

Fresh samples

The latest data comes from examination of a piece of the famous Nakhla meteorite which came down in Egypt, in 1911, breaking up into many fragments.

London's Natural History Museum, which holds several intact chunks of the meteorite, agreed for Nasa researchers to break one open, providing fresh samples.

"It gives people a degree of confidence this had never been exposed to the museum environment," said co-author Colin Pillinger of the UK's Open University.

"I think it's too early to say how [the carbonaceous material] got there... the important thing is that people are always arguing with fallen meteorites that this is something that got in there after it fell to Earth.

"I think we can dismiss that. There's no way a solid piece of carbon got inside a meteorite."

Analysis of the interior revealed channels and pores filled with a complex mixture of carbon compounds. Some of this forms a dark, branching - or dendritic - material when seen under the microscope.

"It's really interesting material. We don't exactly know what it means yet, but it's all over the thin sections of the Nakhla material," said co-author Kathie Thomas Keprta, of Lockheed Martin Corporation and Nasa's Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas.

Indigenous component

Previous studies of the forms - or isotopes - of carbon in the Nakhla meteorite found a component of which more than 75% is lacking any carbon-14.

Since all terrestrial life forms contain some carbon-14, this component was thought to be either indigenous carbon from Mars or ancient meteoritic carbon.

Professor Pillinger and colleagues are carrying out direct isotopic analysis of the carbonaceous material, but he admits terrestrial contamination is occurring when thin slices of the meteorite are made for analysis.

However, the ratio of carbon to nitrogen in the epoxy used to prepare the thin sections is very different from that of the carbonaceous material in the meteorite's veins.

If it is indigenous to Mars, the authors say the "carbonaceous material" came either from another space rock that smashed into Mars hundreds of thousands of years ago, or is a relic of microbial activity.

A resemblance between the material in the meteorite and features of microbial activity in volcanic glass from our planet's ocean floor further support the idea they are biological in origin, says the paper.

If this is the case, the remains of these organisms and their slimy coatings might provide the the carbon-rich material found in Nakhla, the researchers argue.

Peter Buseck, regent's professor of geological sciences at Arizona State University told the BBC News website that he found no strong evidence of a biological origin for the carbon in the meteorite.

He added that it was difficult to determine the origin of carbon in rocks based on microscopy.

The 37th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference runs from 13-17 March in Houston, Texas.

Font: Paul Rincon, http://news.bbc.co.uk